Information Leaflets

British Heart Foundation

Website: https://bhf.org.uk

Call us: 0300 330 3322 Monday to Friday 9am to 5pm

Email: heretohelp@bhf.org.uk

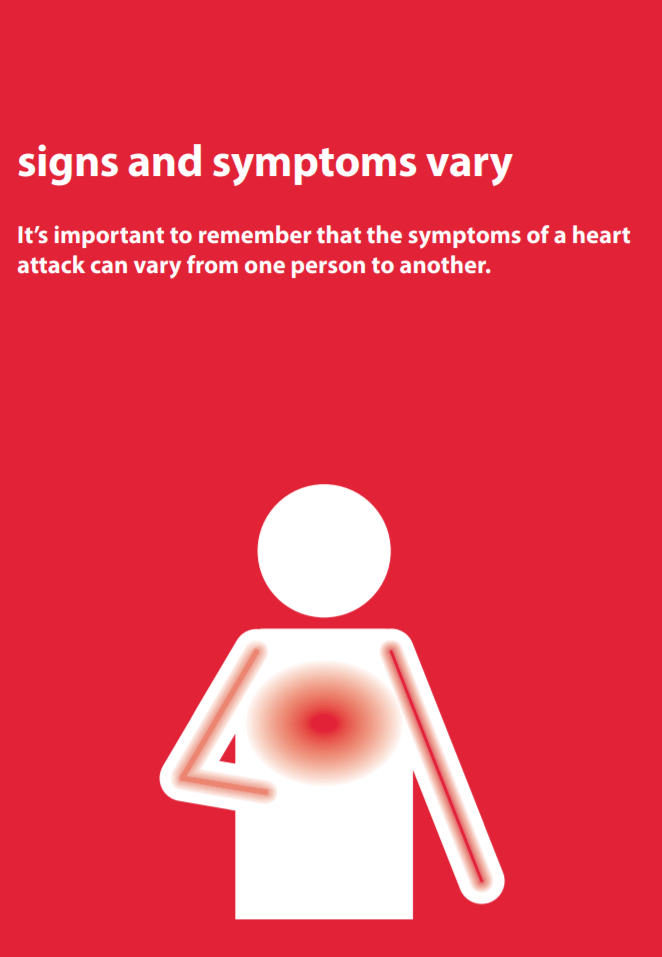

Heart Attacks

click the image below to download the full leaflet

Epilepsy

from Epilepsy Action

website: www.epilepsy.org.uk

freephone helpline 0808 800 5050

click the image below to download the full leaflet

Stoma Care

from Colostomy UK

Stoma helpline: 0800 328 4257

E–mail info@ColostomyUK.org

Website: www.ColostomyUK.org

Further information on Caring for a person with a stoma or Caring for a person with a stoma and dementia <click here>

There are three main types of stoma:

Colostomy

This is the term used to describe an opening from the colon or large

intestine. The stoma is usually sited on the left side of the abdomen. The

output from a colostomy differs from person to person, but tends to be more

solid and often resembles a ‘normal’ stool. A colostomy commonly functions

between one and three times a day.

Ileostomy

This is the term used to describe an opening from the ileum or small

intestine. Typically it is sited on the right of the abdomen. An ileostomy is

more active than a colostomy, functioning three to six times a day and the

output is looser.

Urostomy

This is the term used to describe a stoma for a person’s urine. It is also

sometimes referred to as an ileal conduit. A urostomy is formed by taking a

piece of the patient’s small intestine and attaching the ureters to it, forming

a passageway for urine to pass through. One end of the tube is brought out

through the abdomen to create the urostomy. Usually the person’s bladder

is removed too. A urostomy is normally on the right side of the abdomen.

Unlike a colostomy or an ileostomy, a urostomy functions all the time.

Stoma bags

There are five main types of stoma bag. Each type is made by a number of different

manufacturers. The bag an ostomate uses is determined by the type of stoma they

have and also by what they feel most comfortable wearing and most confident

changing. The importance of the latter should not be underestimated.

• One–piece bag: has an adhesive flange which is attached directly to the

skin. After use the bag is disposed of and a new one fitted.

• Two–piece bag: consists of an adhesive baseplate which is fitted around the

stoma and then the bag either sticks or is clipped to this. Once used, the bag

is removed and disposed of, and a fresh bag attached to the baseplate. The

baseplate is designed to remain attached to the skin for several days.

• Closed bag: are mainly for formed motions. They are more commonly used

by people with colostomies. They are usually changed several times a day.

Some closed bags have a special liner which contains the motions and can

be flushed down the toilet.

• Drainable bag: are mainly for more liquid motions. They are commonly used by

people with ileostomies. They can be worn for longer than closed bags as they

can be emptied through an outlet at the bottom of the bag and then resealed.

• Urostomy bag: are for collecting urine. They are worn by people who have

had a urostomy. A urostomy bag is drainable and has a tap at the bottom.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP)

from PSP Association

for help and advice:

website:

https://pspassociation.org.uk/information-and-support/

email helpline@pspassociation.org.uk

call the helpline on 0300 0110 122

Overview

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a rare progressive condition that can cause problems with balance, movement, vision, speech and swallowing.

It's caused by increasing numbers of brain cells becoming damaged over time.

The PSP Association estimates there are around 4,000 people with PSP living in the UK.

Most cases of PSP develop in people who are over the age of 60.

What causes PSP?

PSP occurs when brain cells in certain parts of the brain are damaged as a result of a build-up of a protein called tau. Tau occurs naturally in the brain and is usually broken down before it reaches high levels. In people with PSP, it isn't broken down properly and forms harmful clumps in brain cells. The amount of abnormal tau in the brain can vary among people with PSP, as can the location of these clumps. This means the condition can have a wide range of symptoms.

The condition has been linked to changes in certain genes, but these genetic faults aren't inherited and the risk to other family members, including the children or siblings of someone with PSP, is very low.

PSP symptoms

The symptoms of PSP usually get gradually worse over time. At first, they can be similar to some other conditions, which makes it difficult to diagnose early on.

Some of the main symptoms of PSP include:

· problems with balance and mobility, including frequent falls

· changes in behaviour, such as irritability or apathy (lack of interest)

· muscle stiffness

· an inability to control eye and eyelid movement, including focusing on specific objects or looking up or down at something

· slow, quiet or slurred speech

· difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

· slowness of thought and some memory problems

The rate at which the symptoms progress can vary widely from person to person.

Diagnosing PSP

There's no single test for PSP. Instead, the diagnosis is based on the pattern of your symptoms.

Your doctor will try to rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as Parkinson's disease. The large number of possible symptoms of PSP also makes it difficult to diagnose correctly and can mean it takes a while to get a definitive diagnosis. You may need to have a brain scan to look for other possible causes of your symptoms, as well as tests of your memory, concentration and ability to understand language. The diagnosis must be made or confirmed by a consultant with expertise in PSP. This will usually be a neurologist (a specialist in conditions affecting the brain and nerves).

Treatments for PSP

There's currently no cure for PSP, but research is continuing into new treatments that aim to relieve symptoms and prevent the condition getting worse. Treatment currently focuses on relieving the symptoms while trying to make sure someone with PSP has the best possible quality of life. As someone with PSP can be affected in many different ways, treatment and care is provided by a team of health and social care professionals working together.

Treatment will be tailored to meet the needs of each individual:

· medication to improve balance, stiffness and other symptoms

· physiotherapy to help with movement and balance difficulties

· speech and language therapy to help with speech or swallowing problems

· occupational therapy to help improve the skills needed for daily activities

· botox (botulinum toxin injections) or special glasses to help with eye problems

· feeding tubes to help manage dysphagia and avoid malnutrition or dehydration

Outlook

There's currently nothing that can be done to stop PSP gradually worsening, although research into new treatments gives hope that this may be possible in the future. Good care and assistance can help someone with PSP to be more independent and enjoy a better quality of life, but the condition will eventually put them at risk of serious complications. It's a good idea to talk to your doctor about what you'd like to happen when the condition reaches this stage.

Difficulty swallowing can cause choking or inhaling food or liquid into the airways. This can lead to pneumonia, which can be life threatening.

Help from a speech and language therapist at an early stage can lower this risk for as long as possible.

As a result of these complications, the average life expectancy for someone with PSP is around 6 or 7 years from when their symptoms start. But it can be much longer, as the timespan varies from person to person.

Symptoms

People with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) develop a range of difficulties with balance, movement, vision, speech and swallowing. The condition tends to develop gradually, which means it can be mistaken for another, more common, condition at first. The symptoms typically become more severe over several years, although the speed at which they worsen varies.

Some of the main symptoms of PSP are outlined below. Most people with the condition won't experience all of these.

Early symptoms

The initial symptoms of PSP can include:

· sudden loss of balance when walking that usually results in repeated falls, often backwards

· muscle stiffness, particularly in the neck

· extreme tiredness

· changes in personality, such as irritability, apathy (lack of interest) and mood swings

· changes in behaviour, such as recklessness and poor judgement

· a dislike of bright lights (photophobia)

· difficulty controlling the eye muscles (particularly problems with looking up and down)

· blurred or double vision

Some people have early symptoms that are very similar to those of Parkinson's disease, such as tremors (involuntary shaking of particular parts of the body) and slow movement.

Mid-stage symptoms

Over time, the initial symptoms of PSP will become more severe. Worsening balance and mobility problems may mean that walking becomes impossible and a wheelchair is needed. Controlling the eye muscles will become more difficult, increasing the risk of falls and making everyday tasks, such as reading and eating, more problematic.

New symptoms can also develop at this stage, such as:

· slow, quiet or slurred speech

· problems swallowing (dysphagia)

· reduced blinking reflex, which can cause the eyes to dry out and become irritated

· involuntary closing of the eyes (blepharospasm), which can last from several seconds to hours

· disturbed sleep

· slowness of thought and some memory problems

· neck or back pain, joint pain and headaches

Advanced stages

As PSP progresses to an advanced stage, people with the condition normally begin to experience increasing difficulties controlling the muscles of their mouth, throat and tongue. Speech may become increasingly slow and slurred, making it harder to understand. There may also be some problems with thinking, concentration and memory (dementia), although these are generally mild and the person will normally retain an awareness of themselves. The loss of control of the throat muscles can lead to severe swallowing problems. This may mean a feeding tube is required at some point to prevent choking or chest infections caused by fluid or small food particles passing into the lungs. Many people with PSP also develop problems with their bowels and bladder functions. Constipation and difficulty passing urine are common, as is the need to pass urine several times during the night. Some people may lose control over their bladder or bowel movements (incontinence).

Diagnosis

It can be difficult to diagnose progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), as there's no single test for it and the condition can have similar symptoms to a number of others. There are also many possible symptoms of PSP and several different sub-types that vary slightly, making it hard to make a definitive diagnosis in the early stages of the condition. A diagnosis of PSP will be based on the pattern of your symptoms and by ruling out conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as Parkinson's disease or a stroke. Your doctor will need to carry out assessments of your symptoms, plus other tests and scans. The diagnosis must be made or confirmed by a consultant with expertise in PSP. This will usually be a neurologist (a specialist in conditions affecting the brain and nerves).

Brain scans

If you have symptoms of PSP that suggest there's something wrong with your brain, it's likely you'll be referred for a brain scan.

Types of scan that you may have include:

· an MRI scan (where a strong magnetic field and radio waves are used to produce detailed images of the inside of the brain)

· a PET scan (this detects the radiation given off by a substance injected beforehand)

· a DaTscan (where you're given an injection containing a small amount of a radioactive material and pictures of your brain are taken with a gamma camera)

These scans can be useful in ruling out other possible conditions, such as brain tumours or strokes.

MRI scans can also detect abnormal changes to the brain that are consistent with a diagnosis of PSP, such as shrinkage of certain areas. Scans that show the build-up of the tau protein in the brain that's associated with PSP are currently under development.

Ruling out Parkinson's disease

You may be prescribed a short course of a medication called levodopa to determine whether your symptoms are caused by PSP or Parkinson's disease. People with Parkinson's disease usually experience a significant improvement in their symptoms after taking levodopa, whereas the medication only has a limited beneficial effect for some people with PSP.

Neuropsychological testing

It's also likely you'll be referred to a neurologist, and possibly also a psychologist for neuropsychological testing. This involves having a series of tests that are designed to evaluate the full extent of your symptoms and their impact on your mental abilities.

The tests will look at abilities such as:

· memory

· concentration

· understanding language

· the processing of visual information, such as words and pictures

Most people with PSP have a distinct pattern in terms of their mental abilities, including:

· poor concentration

· a low attention span

· problems with spoken language and processing visual information

Their memory of previously learned facts isn't usually significantly affected.

Coping with a diagnosis

Being told that you have PSP can be devastating and difficult to take in. You may feel numb, overwhelmed, angry, distressed, scared or in denial. Some people are relieved that a cause for their symptoms has finally been found. There's no right or wrong way to feel. Everybody is different and copes in their own way. Support from your family and care team can help you come to terms with the diagnosis. The PSP Association can give you information and practical advice about living with PSP, as well as providing support to help you cope with the emotional impact of the condition.

PSP Association: helpline on 0300 0110 122 email helpline@pspassociation.org.uk

Treatment

There's currently no cure for progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and no treatment to slow it down, but there are lots of things that can be done to help manage the symptoms. As PSP can affect many different areas of your health, you'll be cared for by a team of health and social care professionals working together. This is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Members of your MDT may include:

· a neurologist (a specialist in conditions that affect the brain and nerves)

· a physiotherapist (who can help with movement and balance difficulties)

· a speech and language therapist (who can help with speech or swallowing problems)

· an occupational therapist (who can help you improve the skills you need for daily activities, such as washing or dressing)

· a social worker (who can advise you about the support available from social services)

· an ophthalmologist or orthoptist (specialists in treating eye conditions)

· a specialist neurology nurse (who may act as your point of contact with the rest of the team)

Some of the main treatments that may be recommended are outlined below.

Medication

There are currently no medications that treat PSP specifically, but some people in the early stages of the condition may benefit from taking levodopa, amantadine or other medications used to treat Parkinson's disease. These medications can improve balance and stiffness for some people with PSP, although the effect is often limited and only lasts for up to a few years. Antidepressants can help with the depression that's often associated with PSP. Some may also help with balance, stiffness, pain and sleep problems. It's important to tell your doctor about the symptoms you're experiencing so they can consider which of these treatments is best for you.

Physiotherapy

A physiotherapist can give you advice about making the most of your remaining mobility using exercise, while making sure you don't overexert yourself. Regular exercise may help strengthen your muscles, improve your posture and prevent stiffening of your joints. Your physiotherapist can advise about equipment that could benefit you, such as a walking frame or specially designed shoes to reduce the risk of slipping and falling. They can teach you breathing exercises to use when you eat to reduce your risk of developing aspiration pneumonia (a chest infection caused by food particles falling into your lungs).

Speech and language therapy

A speech and language therapist (SLT) can help you improve your speech and swallowing problems (dysphagia). They can teach you a number of techniques to help make your voice as clear as possible, and can advise you about suitable communication aids or devices you may need as the condition progresses. Your therapist can also advise you about different swallowing techniques and, working together with a dietitian, they may suggest altering the consistency of your food to make swallowing easier. As your swallowing problems become more severe, you'll need additional treatment to compensate for your swallowing difficulties.

Diet and severe swallowing problems

You may be referred to a dietitian, who'll advise you about making changes to your diet, such as including food and liquids that are easier to swallow, while making sure you have a healthy, balanced diet. For example, mashed potatoes are a good source of carbohydrates, while scrambled eggs and cheese are high in protein and calcium. Feeding tubes may be recommended for severe swallowing problems, where the risk of malnutrition and dehydration is increased. You should discuss the pros and cons of feeding tubes with your family and care team, preferably when your dysphagia symptoms are at an early stage. The main type of feeding tube used is called a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. This tube is placed into your stomach through your tummy during an operation.

Occupational therapy

An occupational therapist (OT) can advise you about how you can increase your safety and prevent trips and falls during your day-to-day activities.

For example, many people with PSP benefit from having bars placed along the sides of their bath to make it easier for them to get in and out. The OT will also be able to spot potential hazards in your home that could lead to a fall, such as poor lighting, badly secured rugs, and crowded walkways and corridors.

Treating eye problems

If you're having problems controlling your eyelids, injections of botulinum toxin (such as Botox) can be used to help relax the muscles of your eyelids. It works by blocking the signals from the brain to the affected muscles. The effects of the injections usually last for up to 3 months. If you're experiencing dry eyes because of reduced blinking, eyedrops and artificial tears can be used to lubricate them and reduce irritation. Glasses with specially designed lenses can help some people with PSP who have difficulty looking down. Wearing dark wraparound glasses can help those who are sensitive to bright light (photophobia).

Palliative care

Palliative care can be offered at any stage of PSP, alongside other treatments. It aims to relieve pain and other distressing symptoms while providing psychological, social and spiritual support.

Advanced care planning

Many people with PSP consider making plans for the future that outline their wishes (both medical and other decisions) and make them known to both their family and the health professionals involved in their care. This can be useful in case you're unable to communicate your decisions later on because you're too ill, although it's voluntary and you don't have to do it if you don't want to.

Issues that you may want to cover might include:

· whether you want to be treated at home or in a hospice or hospital when you reach the final stages of PSP

· the type of painkillers you'd be willing to take

· whether you'd be willing to use a feeding tube if you were no longer able to swallow food and liquid

· whether you're willing to donate any of your organs after you die

· whether you'd be willing to be resuscitated by artificial means if you experienced respiratory failure (loss of lung function)

If you decide to discuss these issues, they can be written down in a number of ways:

· advance decision to refuse treatment

· advance statement

· emergency healthcare plan

· lasting power of attorney

Your care team can provide you with more information and advice about these decisions and how best to record them.

Care and support

If someone you know develops PSP, you may need information and advice about caring for them. The Care and support guide has a wide range of useful information about all aspects of caring for others, and advice for carers themselves.

You can also contact the PSP Association for help and advice:

email helpline@pspassociation.org.uk

call the helpline on 0300 0110 122

The Parkinson's nurse at your local hospital may be able to provide you with useful information and support.